Meet the Tasmanian Devil

The Tasmanian Devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) is the world’s largest surviving carnivorous marsupial. Known for its jet-black fur, bone-crunching jaws, and spine-chilling screams, this iconic animal has become a symbol of Australia’s unique wildlife and of one of the most unusual conservation battles in the world.

Scientific Name: Sarcophilus harrisii

Phylum: Chordata

Order: Dasyuromorphia

Genus: Sarcophilus

Kingdom: Animalia

Class: Mammalia

Family: Dasyuridae

Species: S. harrisii

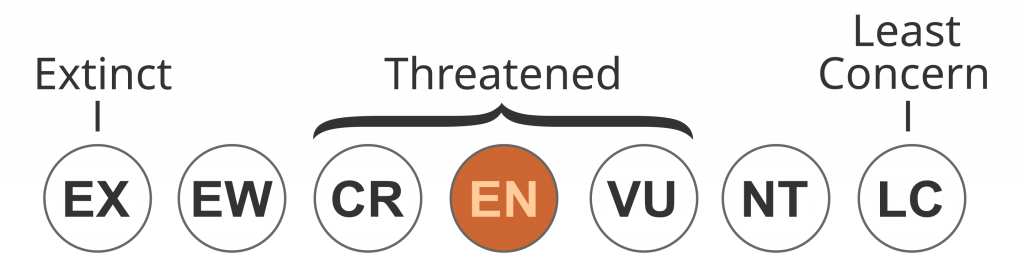

IUCN Redlist Status:

Tasmanian Devils are listed by the IUCN as endangered because of their small population of 25,000. Their population is in decline because of devil facial tumour disease, habitat loss and fragmentation, and climate change.

The Black-Spirited Carnivore

The Tasmanian Devil is a stocky animal about the size of a small dog, weighing between 13 and 26 pounds. Males are generally larger than females. They have coarse black fur, sometimes with distinctive white patches on the chest or rump. Despite their fierce reputation, devils are shy and mostly nocturnal scavengers. Their powerful jaws and broad heads allow them to crush bones and consume entire carcasses, leaving nothing behind. Devils also communicate with spine-chilling screeches, growls, and hisses, which often sound much fiercer than the animal truly is.

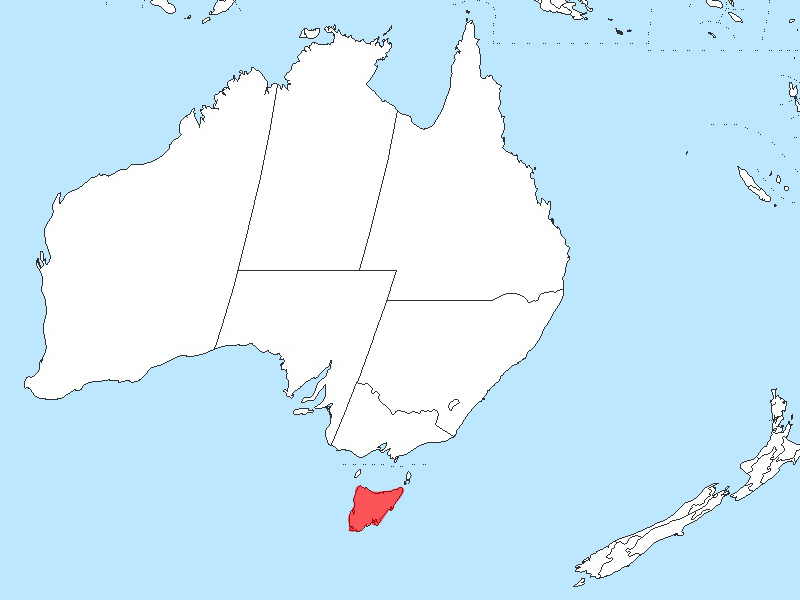

Where Do They Live?

Tasmanian Devils live exclusively on the island of Tasmania, located off the southeastern coast of Australia. They inhabit diverse environments, including coastal scrublands, dry forests, agricultural areas, and mountainous regions. Devils shelter in dense vegetation, caves, hollow logs, or burrows during the day and roam long distances at night in search of food.

The Tumor That Threatens Their Existence

Since the mid-1990s, Tasmanian Devils have been devastated by a highly unusual disease: Devil Facial Tumour Disease (DFTD). This aggressive cancer grows as tumors on the face and inside the mouth, making it impossible for affected devils to eat. Uniquely, the disease is transmitted from animal to animal through biting, especially during social interactions and feeding. The disease has caused local population declines of more than 80% in some regions. However, recent research suggests devils may be evolving resistance, and some populations are beginning to show signs of natural immunity or slowed tumor growth. Conservationists have also established disease-free insurance populations in fenced enclosures and offshore islands to protect the species from extinction.

Devils at The Dinner Table

Tasmanian Devils are primarily scavengers, feeding on carrion such as wallabies, wombats, and birds. However, they can hunt small prey, including insects, frogs, and reptiles. Thanks to one of the strongest bites per body size of any mammal, devils can consume bones, fur, and organs, leaving virtually nothing behind. This makes them essential “clean-up crews” in Tasmania’s ecosystems.

Living Together… Or Not

While devils are often thought of as solitary, they will gather in groups around large carcasses. When this happens, intense squabbles break out as devils scream, lunge, and bare their teeth at each other in displays of dominance. These vocalizations and body language help establish feeding order and avoid serious injuries. Tasmanian Devils breed once per year, usually around March. Females can give birth to 20–40 tiny, underdeveloped young, but only four typically survive because the mother has only four teats in her pouch. The surviving joeys remain in the pouch for about four months and then stay in a den until weaned at around six months old. Young devils become independent by nine months and are capable hunters and scavengers.

Here are 5 fun facts about Tasmanian Devils that you can add to your bag of information:

The devil’s reputation for ferocity inspired the cartoon character “Taz” from Looney Tunes.

Devils glow under ultraviolet light, revealing mysterious patterns scientists are still investigating.

A devil’s bite is strong enough to crush bones, with a bite force comparable to that of a dog four times its size.

Devils use their tails as fat storage; a thin tail is a sign of poor health.

Early European settlers named them “devils” because of their chilling screams and fierce temper.

Threats to their survival

Beyond Devil Facial Tumour Disease, Tasmanian Devils face additional threats, including:

- Habitat Loss: Agricultural development and urban expansion reduce devil’s habitat.

- Vehicle Collisions: Devils frequently become roadkill while scavenging carcasses on roads.

- Competition with Invasive Species: Introduced predators like feral cats and foxes compete for food and can spread diseases.

How You Can Help Save the Tasmanian Devil

- Support Conservation Groups: Organizations such as the Save the Tasmanian Devil Program work tirelessly to protect this iconic species.

- Spread Awareness: Educate friends and family about the Tasmanian Devil and the importance of conserving unique wildlife.

- Adopt a Devil: Many programs offer symbolic adoptions that fund research and conservation.

- Shop at Artsefact: Part of the proceeds go towards wildlife and habitat conservation.

Buy Art & Save Wildlife

10% of all profits support wildlife and habitat conservation efforts, so every artwork you collect helps protect the planet.

Tasmanian Devil Factsheet

Would you like a Tasmanian Devil fact sheet?

- Sign up for our newsletter for exclusive updates and wildlife conservation tips (Your welcome email has your Password for the Portal)

- Visit https://artsefact.com/factsheets/ where you can access and download ALL Factsheets & Gain Early Access to NEW Factsheets

Here’s how you can gain access:

Resources

- The IUCN List of Threatened Species – https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/40540/10331066

- National Geographic – https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/gruesome-cancer-afflicting-tasmanian-devils-may-be-waning

- Tasmanian Government – https://nre.tas.gov.au/wildlife-management/fauna-of-tasmania/mammals/carnivorous-marsupials-and-bandicoots/tasmanian-devil

- PBS – https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/tasmanian-devils-cancer-extinction